In part one we explored the concepts of existence and identity. That was followed, in part 2, by a look at the major influences that lead to the idea that the soul is immortal. This entry will explore alternative understandings of the soul for consideration.

In the last post we saw that, despite different underlying philosophical foundations, Augustine and Aquinas affirm that the person is a composite of body and soul. They also both affirm that the soul, an incorporeal intellect and the principle of life, is naturally immortal (or incorruptible). In a moment we will see that both theologians will be careful to ground the existence of the soul in God and His will rather then in itself. In doing so, we might, with a degree of irony, call both Augustine and Aquinas advocates of a conditional immortality.

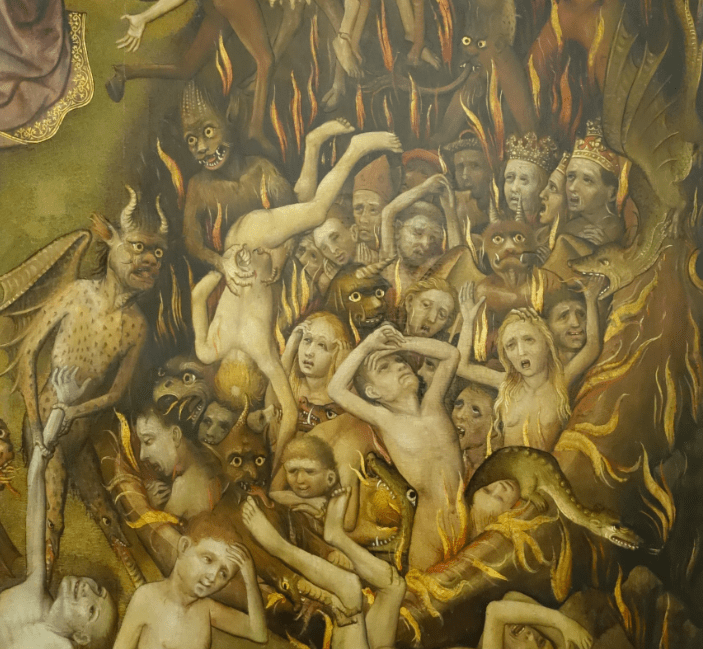

The punishment of the damned will never come to an end

Before one scoffs at that and considers it a foolish claim, let me make it abundantly clear that both of these theologians affirm that the wicked will suffer eternal conscious torment (ECT).

pain can exist only

in a living subject 1

– Augustine

Augustine notes that in his day there is debate about the fate of the wicked. He spends the greater part of Book XXI of The City of God making the case that “the soul [of the wicked] will neither be able to enjoy God and live, nor to die and escape the pains of the body.” 2

… to say in one and the same sense, life eternal shall be endless, punishment eternal shall come to an end, is the height of absurdity. Wherefore, as the eternal life of the saints shall be endless, so too the eternal punishment of those who are doomed to it shall have no end.3

In the supplement to the Summa Aquinas argues “the damned can prefer ‘not to be’ according to their deliberate reason” which would be to have “relief from a painful life”.4 However “it is inadmissible that the punishment of the damned will ever come to an end.” 5

The disposition of hell will be such as to be adapted to the utmost unhappiness of the damned. Wherefore accordingly both light and darkness are there, in so far as they are most conducive to the unhappiness of the damned. 6

Having established that Augustine and Aquinas were deeply committed to ECT, why might we consider them advocates of conditional immortality?

The conditional existence of an immortal soul

In the City of God, Augustine does admit that that everything that exists does so by God’s creating and sustaining power.

It is His occult power which pervades all things, and is present in all without being contaminated, which gives being to all that is, and modifies and limits its existence; so that without Him it would not be thus, or thus, nor would have any being at all …

if He were, so to speak, to withdraw from created things His creative power, they would straightway relapse into the nothingness in which they were before they were created 7

In one of his many explorations on Genesis, Augustine would reiterate this idea:

But [God] rested like this in such a way as to continue from then on and up till now to operate the management of things that were then set in place, not as though at least on that seventh day his power was withheld from the government of heaven and earth and of all things he established; if that had been done, they would forthwith have collapsed into nothingness. It is the creator’s power … that causes every created thing to subsist.

… the conclusion follows that if he withdraws this work from things, we will neither live nor move nor be. 8

Augustine here is stating the principle: created things exist due to an ongoing dependence on the presence of God’s power

This principle can also be found in the works of Aquinas. In refuting the idea that “whatever is out of nothing can return to nothingness”, Aquinas will argue that the soul has “an incorruptible substantial life.” He does go on to admit that even the incorruptible soul, that does not decay on its own, owes its existence to the sustaining power of the Creator.

[The Creator] can produce something out of nothing, so when we say that a thing can be reduced to nothing, we do not imply in the creature a potentiality to non-existence, but in the Creator the power of ceasing to sustain existence.9

He repeats this principle in the first article of question 104.

all creatures need to be preserved by God. For the being of every creature depends on God, so that not for a moment could it subsist, but would fall into nothingness were it not kept in being by the operation of the Divine power.10

In the second article he also explicitly notes his agreement with Augustine’s statement in the Literal Meaning of Genesis (quoted above).

Aquinas makes it clear in the third article of question 104 that existence of a creature is conditional – dependent on the will of God to continually sustain it thus preventing it from ceasing to exist.

Therefore that God gives existence to a creature depends on His will; nor does He preserve things in existence otherwise than by continually pouring out existence into them, as we have said. Therefore, just as before things existed, God was free not to give them existence, and not to make them; so after they have been made, He is free not to continue their existence; and thus they would cease to exist; and this would be to annihilate them.11

It is in this sense we might suggest that Augustine and Aquinas hold to a conditional immortality. All entities, including the soul, only continue in existence if and only if God wills that they should continue and uses His power to bring it about.

Some early alternative views

Justin Martyr, a Christian philosopher in the second century, was a student of philosophy. His search led him to Christ. During his search for truth he studied many different schools of philosophy and is familiar with Plato’s theories on the soul. In his dialogue with the old man in the work Dialogue with Trypho he shares his view on the soul.

Justin: [The soul] is both unbegotten and immortal, according to some who are styled Platonists.

…

Old man: … if the world is begotten, souls also are necessarily begotten; and perhaps at one time they were not in existence, for they were made on account of men and other living creatures …

Justin: This seems to be correct.

Old Man: They are not, then, immortal?

Justin: No…

…

Justin: Is what you say, then, of a like nature with that which Plato in Timæus hints about the world, when he says that it is indeed subject to decay, inasmuch as it has been created, but that it will neither be dissolved nor meet with the fate of death on account of the will of God? Does it seem to you the very same can be said of the soul, and generally of all things? For those things which exist after God, or shall at any time exist, these have the nature of decay, and are such as may be blotted out and cease to exist; for God alone is unbegotten and incorruptible, and therefore He is God, but all other things after Him are created and corruptible. …

Old Man: It makes no matter to me whether Plato or Pythagoras, or, in short, any other man held such opinions. For the truth is … that the soul lives, no one would deny. But if it lives, it lives not as being life, but as the partaker of life; but that which partakes of anything, is different from that of which it does partake. Now the soul partakes of life, since God wills it to live. Thus, then, it will not even partake [of life] when God does not will it to live. For to live is not its attribute, as it is God’s ... 12

Justin would readily affirm, with Augustine and Aquinas, that the soul exists on the condition that God wills that it should exist. Although his treatment is not as deep and thorough as Augustine or Aquinas, we can understand him as making the following points, which would not align with these two later thinkers:

- The soul is not naturally immortal, left alone it would decay

- The soul is not essentially life, but participates in life if God wills

Tatian, another second century Christian, would also affirm that the soul is not in itself immortal, but requires “the power [of God] that makes souls immortal”.13 It should be noted that despite his metaphysical understanding of the soul he appears to use language that can be taken as alignment with ECT.

The soul is not in itself immortal, O Greeks, but mortal. Yet it is possible for it not to die. If, indeed, it knows not the truth, it dies, and is dissolved with the body, but rises again at last at the end of the world with the body, receiving death by punishment in immortality. But, again, if it acquires the knowledge of God, it dies not, although for a time it be dissolved. 14

Irenaeus, yet another second century Christian, like Justin, saw the soul as having life bestowed on it by God, rather than being the principle of life.

For life does not arise from us, nor from our own nature; but it is bestowed according to the grace of God. … But as the animal body is certainly not itself the soul, yet has fellowship with the soul as long as God pleases; so the soul herself is not life, but partakes in that life bestowed upon her by God. Wherefore also the prophetic word declares of the first-formed man, He became a living soul, teaching us that by the participation of life the soul became alive; so that the soul, and the life which it possesses, must be understood as being separate existences. When God therefore bestows life and perpetual duration, it comes to pass that even souls which did not previously exist should henceforth endure [for ever], since God has both willed that they should exist, and should continue in existence.15

Like the other theologians we have considered, Irenaeus affirms that the soul will continue in existence only if God should will that it does.

Irenaeus, unlike Tatian, seems to affirm annihilationism.

he who shall preserve the life bestowed upon him, and give thanks to Him who imparted it, shall receive also length of days for ever and ever. But he who shall reject it, and prove himself ungrateful to his Maker, … deprives himself of [the privilege of] continuance for ever and ever. … [they], shall justly not receive from Him length of days for ever and ever.16

Jumping ahead in time, we find Athanasius, the bishop noted for his role in defending the Trinity in the fourth century, holding views similar to Justin Martyr (see this post for details). For him, the “human being is by nature mortal, having come into being from nothing.” Mankind was created to remain in “the comprehension of God” and thus possess eternal being but having transgressed was “returned to the natural state.” 17 From this we can see that a person, inclusive of the soul, would not be naturally immortal, but left alone would decay into non-existence.

Where does that leave us?

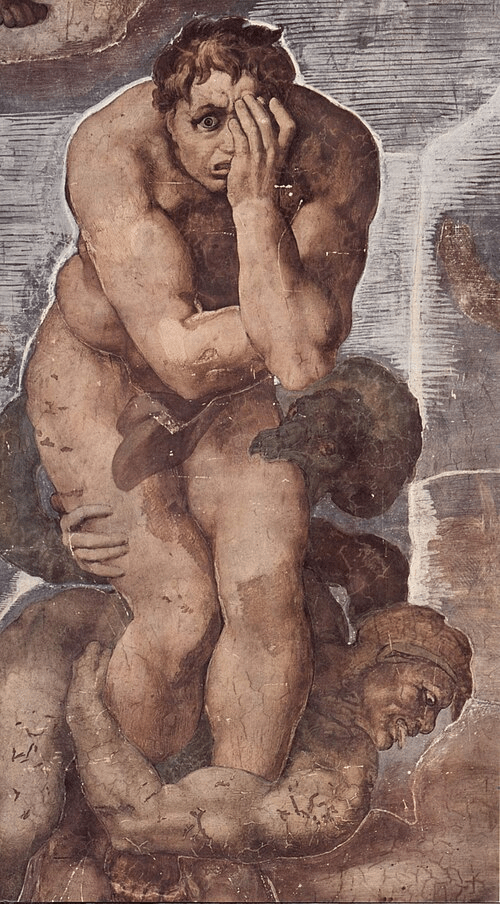

Even granting Augustine’s and Aquinas’s claim that the soul is naturally immortal, it does not necessarily follow that God must sustain the wicked forever. The claim that the soul is naturally or intrinsically immortal only excludes intrinsic corruption, not annihilation due to God’s withdrawal of sustaining power. It is undeniable that Augustine and Aquinas affirm that God in fact sustains the wicked eternally keeping them alive to endure punishment. It is also undeniable that this conclusion is not a metaphysical necessity.

Metaphysically there are two possibilities.

The first is that, God continues to “pour out existence” keeping the person, as body and soul, alive so that they will experience a pain that will not kill. 18

The second is that, God can, in principle and practice, withdraw His sustaining power after a fixed term of punishment and allow a person to die. In dying the person, in body and soul, would cease to exist.

The claim then, at this point, is simple. Any argument that a person will live in torment forever because the soul is immortal or that it cannot cease to exist is overstating the case. God can destroy the soul. To deny that is to deny His omnipotence. Therefore it is metaphysically possible that the wicked, after suffering in accordance with their deeds, would eventually be destroyed and cease to exist. Not even these great and influential thinkers, Augustine and Aquinas, held that God created a soul so deathless He couldn’t kill it. Other philosophical arguments and theological commitments would need to be used to defend either the ECT or CI positions.

- Augustine, City of God Book XXI.3

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/120121.htm ↩︎ - Augustine, City of God Book XXI.3 ↩︎

- Augustine, City of God Book XXI.23 ↩︎

- Aquinas, Summa supplement Q 98.3

https://www.newadvent.org/summa/5098.htm ↩︎ - Aquinas, Summa supplement Q 99.2

https://www.newadvent.org/summa/5099.htm ↩︎ - Aquinas, Summa supplement Q 97.4

https://www.newadvent.org/summa/5097.htm ↩︎ - Augustine, City of God Book XII.25

(https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/120112.htm) ↩︎ - Augustine, On Genesis (p 274-275) New City Press

Literal Meaning of Genesis Book IV.12 ↩︎ - Aquinas, Summa 1.Q75.6

https://www.newadvent.org/summa/1075.htm ↩︎ - Kreeft, Peter. Summa of the Summa: The Essential Philosophical Passages of the Summa Theologica (pp. 212-213). Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition.

Summa 1.104.1 ↩︎ - Ibid (p 214)

Summa 1.104.3 ↩︎ - Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, excerpts from chap 5 and 6 ↩︎

- Tatian, Against the Greeks chap 15 ↩︎

- Tatian, Against the Greeks chap 13 ↩︎

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies Book II chapter 34 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Athanasius, Saint, Patriarch of Alexandria. On the Incarnation: Saint Athanasius (Popular Patristics Series Book 44) (p. 50-51). St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. ↩︎

- Augustine, City of God Book XXI.3 ↩︎