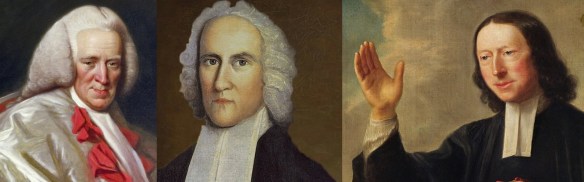

This post is part 5 of a series that has explored the three essays on the topic Liberty and Necessity by John Wesley, Jonathan Edwards and Lord Kames. This series started with this post Wednesday with Wesley: Thoughts Upon Necessity

This series started with a look at John Wesley’s critique of the Lord Kames’ views on Necessity, Liberty and Moral Obligation. Wesley focused on two aspects of Lord Kames’ view and contrasted them with the theme of judgment in Scripture. The first was that Kames required a Liberty of Contingence for there to be moral accountability and the second was that, according to the Scot, we don’t have it.

Despite a good deal of agreement between Lord Kames and Jonathan Edwards, particularly on our actions being morally necessary, we found that Edwards assailed the position held by Lord Kames as well. The main point Edwards made was that we do have liberty, but it is not a Liberty of Contingence. He would then argue that a Liberty of Moral Necessity was not only compatible with moral accountability for our actions, but that it is the only rational way to defend that we are under Moral Obligation.

As, Wesley, in his essay, has laid out the final conclusions against the Lord Kames (see part 1), he writes “Mr. Edwards has found out a most ingenious way of evading this consequence.”1 This “most ingenious way” around Wesley’s conclusion was to argue with “deep, metaphysical reasoning” for a different definition of liberty. Anyone who has tackled Edward’s Inquiry would have to agree with Wesley, it is a dense treatise that specializes in the wrangling of words and ideas.

Wesley does not directly quote Edwards but does correctly identify how he escapes the predicament of Lord Kames’ position.

Such absurdities [as a judgment when men are not morally accountable] follow, from the scheme, of Necessity. But Mr, Edwards, has found a most ingenious way of evading this consequence. …. if the actions of men were involuntary, the consequence would inevitably follow; they could not be either good or evil … [but]… The actions of men are quite voluntary; the fruit of their own will. … Now if men voluntarily commit theft, adultery or murder, certainly the actious are evil, and therefore punishable. And if they voluntarily serve GOD, and help their neighbors, the actions are good, and therefore rewardable. 2

Edwards claims that our actions, despite being morally necessary, are voluntary choices. Therefore we should be morally accountable for them.

Wesley, in crafting his summary, may have drawn on Edward’s clear assertions that the act of the Will, consisting of “some inclination of the soul”, is voluntary action. 3

the Will’s determining between [one thing rather than another], is a voluntary determination; but that is the same thing as making a choice. 4

and

There is scarcely a plainer and more universal dictate of the sense and experience of mankind, than that, when men act voluntarily, and do what they please, then they do what suits them best, or what is most agreeable to them. 5

If we remember, Edwards has defined Liberty as the power to do as one pleases. That is equated, here, with the idea of acting voluntarily. Later in his Inquiry, Edwards ties having liberty to having moral accountability.

The common people, in their notion of a faulty or praiseworthy deed or work done by any one, do suppose that the man does it in the exercise of liberty. But then their notion of liberty is only a person’s having opportunity of doing as he pleases. … the more he does either with full and strong inclination, the more is he esteemed or abhorred, commended or condemned.6

Stepping back, Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley, and even the Lord Kames, can be said to affirm that liberty is necessary for moral accountability. However, the differences in how these theologians define and understand the term liberty render this statement meaningless as it is rife with semantic ambiguity. Further exploration is required as each is saying something quite different than the other.

It is worth noting that Lord Kames and John Wesley, contra Edwards, are more closely aligned on how they understand the term liberty, as both would argue it is “opposed to moral necessity.” 7 But even these gentlemen, despite agreeing that contingency involves an action that “may be or may not be”, would disagree as to whether this was attributable to chance.

What is a moral agent?

Both Edwards and Wesley affirm that most physical objects as found in nature, such as the sun, are not moral agents. Both will root this in the fact that these types of objects do not have a choice in what they do. Edwards emphasizes their lack of a will, while Wesley emphasizes the necessity of their actions as the major reason to reject moral accountability, but both are essentially saying the same thing and for the same reasons: moral agents must have a choice.

Here is how Edwards explains that using the sun and fire as examples:

The sun is very excellent and beneficial in its action and influence on the earth, in warming it, and causing it to bring forth its fruits; but it is not a moral agent [having no moral faculty, as is the will]; its action, though good, is not virtuous or meritorious. Fire that breaks out in a city, and consumes great part of it, is very mischievous in its operation, but is not a moral agent: what it does is not faulty or sinful, or deserving of any punishment.8

Here is how Wesley, explains it, using the sun and the sea as examples:

The Sun does much good: but it is no Virtue: but he is not capable of Moral Goodness. Why is he not? For this plain reason, because he does not act from Choice. The Sea does much harm: it swallows up thousands of men; but it is not capable of Moral Badness: because it does not act by choice, but from a necessity of Nature. If indeed one or the other can be said to act at all. Properly speaking it does not: It is purely passive: it is only acted upon by the Creator; and must move in this manner and no other, seeing it cannot resist his Will 9

From these examples, Wesley rightly recaps Edward’s view in saying: “if the actions of men were involuntary, the consequence would inevitably follow; they could not be either good or evil.”10

However, the differences in how these theologians define and understand the term voluntary choice render the statement: moral agents must act from choice just as rife with semantic ambiguity as the idea that liberty is necessary for moral accountability.

What is a choice?

In Part 1, section 1 and section 2 of his Inquiry, Edwards asserts that “an act of the will is the same as an act of choosing or choice.” 11 He is also content to affirm that a choice is when “the soul either chooses or refuses” and that it is when “the mind chooses one thing rather than another.” He then comes full circle in stating that when the mind makes “its choice [it] is properly the act of the Will.

Although he bounces between the terms “will”, “mind” and “soul”, he concludes that the “act of the will”, the “preponderation of the mind”, the “inclination of the soul” and volition are all ways of saying that a person makes a choice for one thing rather than another. The thing, or object, that is chosen is then described as “that which is most agreeable”, “viewed as good”, or “seems pleasing”. 12

Here is a concise look at Edwards main points:

- 1) an act of the Will is the same as an act of choosing or choice 13

- 2) when the mind makes a choice it is properly the act of the Will 14

- 3) a man never, in any instance, wills any thing contrary to his desires 15

- 4) determining the Will [is to] cause the choice to be thus, and not otherwise 16

- 5) determining [occurs when the] choice is directed to, and fixed upon, a particular object … rather than another. 17

- 6) The determination of the choice to a particular object is the effect of some cause18

- 7) the Will is determined by the strongest motive 19

Edwards is clear that he denies a “self-determining power in the Will … whereby it determines its own volitions; so as not to be dependent, in its determinations, on any cause without itself, nor determined by any thing prior to its own acts.” 20 The idea of a “self-determining power” is considered absurd and inconsistent by Edwards. 21

For Edwards, choice, as an act of the will, is the effect produced by a cause. And the cause is the strongest motive. This motive directs the will to one object over all others.

So what is a motive?

Edwards defines that in his Inquiry.

By motive, I mean the whole of that which moves, excites, or invites the mind to volition, whether that be one thing singly, or many things conjunctly. Many particular things may concur and unite their strength to induce the mind; and when it is so, all together are, as it were, one complex motive.22

That which moves the will to a particular object and not another is that which is presented to the mind’s view or perceiving faculty as “most agreeable”. What is this thing, singular or many, that causes a particular object to be more agreeable than all others to our mind is, Edwards admits, no easy thing to describe.

but that the act of volition itself is always determined by that, in or about the mind’s view of the object, which causes it to appear most agreeable. I say in or about the mind’s view of the object, because what has influence to render an object in view agreeable, is not only what appears in the object viewed, but also the manner of the view, and the state and circumstances of the mind that views. Particularly to enumerate all things pertaining to the mind’s view of the objects of volition, which have influence in their appearing agreeable to the mind, would be a matter of no small difficulty, and might require a treatise by itself, and is not necessary to my present purpose..23

Conveniently, Edwards sets aside the challenge of exploring what determines or causes that which appears most agreeable to a person in their mind. However, this is where the heart of the tension in what constitutes liberty and moral accountability lies. Earlier in his Inquiry, Edwards had narrowed the definition of choice, focusing only on “the power to do what one wills”, purposely leaving out of his definition of choice what, if anything, causes the motive which in turn causes the choice “to be thus, and not otherwise.”

But one thing more I would observe concerning what is vulgarly called liberty ; namely, that power and opportunity for one to do and conduct as he will, or according to his choice, is all that is meant by it; without taking into the meaning of the word, any thing of the cause or original of that choice, or at all considering how the person came to have such a volition, …. Let the person come by his volition or choice how he will, yet, if he is able, and there is nothing in the way to hinder his pursuing and executing his will, the man is fully and perfectly free, according to the primary and common notion of freedom24

This notion of choice as the power to do as one wills, without considering how the strongest motive comes to be, is the foundation for Edwards definition of liberty, specifically a Liberty of Moral Necessity (for more see part 4 in this series).

Liberty, as I have explained it is the Power , Opportunity , or Advantage that any one has to do as he pleases, or conducting, IN ANY RESPECT, according to his Pleasure; without considering how his Pleasure comes to be as it is25

Back to the mistake

Edwards sees the determination of the will by the strongest motive as an act of moral necessity that makes an action certain. That means, that for Edwards, a voluntary choice is morally necessitated to find a particular object agreeable by its prior cause.

Moral necessity may be as absolute as natural necessity: that is, the effect may be as perfectly connected with its moral cause as a natural necessary effect is with its natural cause.26

Edwards may claim a morally necessary act is voluntary, being an effect of our will because it was something that the agent possessing this Will was pleased to do. However, Wesley, again correctly, draws attention to Edwards limited focus, going to so far as to suggest that the Inquiry based on faulty reasoning. The narrowing of his argument on the strongest motive causing the act of the will while ignoring details around the “sure and perfect connection between [the] moral cause” that determined the strongest motive invites questions about whether these inclinations can rightly be said to be what the actor has chosen.

I cannot possibly allow the consequence, upon Mr. Edwards’s supposition [that a morally necessary act is voluntary]. Still I say, if they are necessitated to commit robbery or murders they are not punishable for committing it. But you answer, “Nay, their actions are voluntary the fruit of their own will.“ If they are, yet that is not enough, to make them either good or evil, For their will, on your supposition, is irresistibly impelled; so that they cannot help willing thus or thus. If so, they are no more blamable for that Will, than for the actions which follow it. There is no blame, if they are under a necessity of willing. There can be no moral Good or Evil, unless they have Liberty as well as Will, which is entirely a different thing. And the not adverting to this, seems to be the direct occasion, of Mr. Edwards whole mistake. 27

We will explore John Wesley’s ideas on Liberty and the Will in the next post.

[Continuing Thoughts Upon Necessity (part 6)]

- Wesley, John, “Thoughts on Necessity“, 22

source: https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_thoughts-upon-necessity_wesley-john_1774 ↩︎ - Wesley, 22 ↩︎

- Edwards, Jonathan, Freedom of the Will, Part 1 Section 4, 26 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 1, 2 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 2, 14 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 4 Section 4, 242 ↩︎

- Kames, 175, Wesley, 16

Where Kames will write “liberty as opposed to moral necessity“, we see Wesley affirm something similar in “if he does not act from choice but Necessity ↩︎ - Edwards, Jonathan, Freedom of the Will, Part 1 Section 5, 34

source:https://archive.org/details/freedomofwill0000revj ↩︎ - Wesley, 16 ↩︎

- Wesley, 22 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 1, 1 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 2, 6-8 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 1, 1 ↩︎

- Ibid, 2 ↩︎

- Ibid, 4 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 2, 5 ↩︎

- Ibid, 5-6 ↩︎

- Ibid, 6 ↩︎

- Ibid, 6 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 5, 33 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 2 Section 4, 58 ↩︎

- Ibid, 6 ↩︎

- Ibid, 10 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 5,33 ↩︎

- Remarks, 2 ↩︎

- Edwards, Part 1 Section 4, 25 ↩︎

- Wesley, 22-23 ↩︎