Having read Wesley’s “Thoughts Upon Necessity”, I decided to read more of Lord Kames’ essay “On Liberty and Necessity”. This post is a follow-up to the post Wednesday with Wesley: Thoughts Upon Necessity, which introduces us to both the essays.

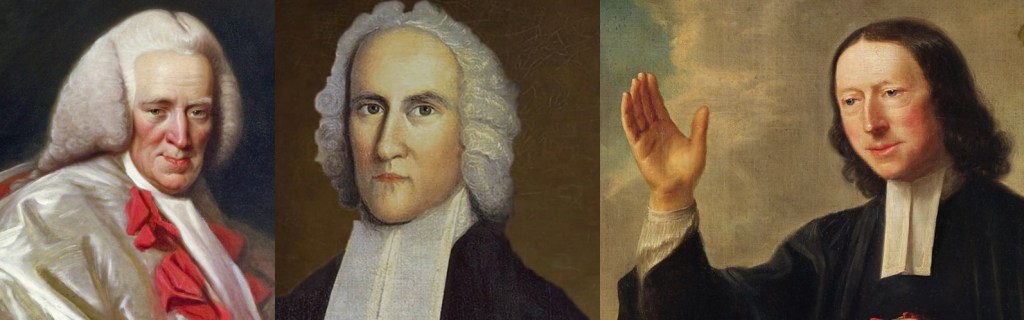

In the last post, we highlighted portions of Lord Kames’ position to provide enough content in which to frame Wesley’s argument against it. We also provided a condensed format of Wesley’s argument. In this post we will focus on Kames’ view that we are given a “delusive Sense of a Liberty of Contingence, to be the Foundation of all the Labour, Care and Industry of Mankind” and the responses to that idea from both Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley.1

The position taken by Lord Kames

In the prior post we relied primarily on Wesley’s quotes from Kames’ essay. Here we will add a more expansive summary taken directly from Kames’ work “Liberty and Necessity“. 2

Lord Kames will assert a basic principle: “that nothing can happen without a cause” and that “nothing that happens is conceived as happening of itself, but as an effect produced by some other thing.” 3

This principle is applied to both the natural and moral worlds, however, it will be made clear that the fixed laws that govern each are not the same.

Taking a view of the natural world we find all things there proceeding in a fixed and settled train of causes and effects. It is a point which admits of no dispute, that all the changes produced in matter, and all the different modifications it assumes, are the result of fixed laws. Every effect is for precisely determined, that no other effect could, in such circumstances, have possibly resulted from the operation of the cause: which holds even in the minutest changes of the different elements [as these are the] necessary effect of pre-established laws.4

The result, Kames admits, is that “in the material world, there is nothing that can be called contingent but everything must be precisely what it is.” In the moral world, which is the realm in which “man is the actor”, we find things “do not appear so clearly.”

Just as the material world is subject to mechanical laws resulting in physical necessity, the moral world is just as much under a “necessity to act”. The actions of man are just as fixed as “the revolution of seasons and the rising and setting of the sun”. They are just as certain as the fact that a “stone [will] fall to the ground when it is dropped from the hand”. However, according to Kames, the moral world doesn’t operate under the mechanical laws that drive the “train of causes and effects” in the world around us. It operates under a different set of laws.

Lord Kames spends several pages defending the principle that the moral world is run by the fixed law that our actions are always the result of a motive, specifically the strongest. Kames doesn’t deny that there are other motives, “however silent or weak” but at the moment of acting, it is the “motive which has the greatest influence” upon which “the choice being made is founded.”

[In the moral world] it follows of consequence, that the determination must result, from that motive, which has the greatest influence for the time; or from what appears the best and most eligible upon the whole. If motives be of very different kinds, with regard to strength and influence, which we feel to be the case; it is involved in the very idea of the strongest motive, that it must have the strongest effect in determining the mind. This can no more be doubted of, that that, in a balance, the greater weight must turn the scale.5

The moral world operates according to a chain of cause and effect. The act is the effect of the will, and the choice of the will is the effect of the the strongest motive. That should turn our attention to the motive, which, according to Kames, is “not under our power or direction.”

In short, if motives are not under our power or direction, which is confessedly the fact, we can, at bottom, have no liberty. We are so constituted, that we cannot exert a single action, but with some view, aim or purpose. At the same time, when two opposite motives present themselves, we have not the power of an arbitrary choice. We are directed, by a necessary determination of our nature to prefer the strongest motive. … in the end, [our mind must] necessarily be determined to the side of the most powerful motive 6

Kames will then add another link in the chain. Noting that our “liberty” is founded on the fact that we act according to our inclination and choice. These being caused by the strongest motive.

In this lies the liberty of our actions, in being free from constraint, and in acting according to our inclination and choice. But as this inclination and choice is unavoidably caused or occasioned by the prevailing motive; in this lies the necessity of our actions, that, in such circumstances, it was impossible we could act otherways. In this sense all our actions are equally necessary. 7

If the motives are outside of our power, then who or what has power over them?

We find here that it is the Deity that upholds the principles that while “these laws remain in their force, not the smallest link of the universal chain of causes and effects can be broken, nor any one thing be otherways then it is.”

The Deity is the First Cause of all things. He formed, in His infinite mind, the great plan or scheme, upon which all things were to be governed; and put it in execution, by establishing certain laws, both in the natural and moral world, which are fixt and immutable. By virtue of these all things proceed in a regular train of causes and effects, bringing about those events which are contained in the original plan, and admitting the possibility of no other. This universe is a vast machine, winded up and set a-going. The several springs and wheels act unerringly one upon another. The hand advances, and the clock strikes, precisely as the Artist determined. 8

How does God bring about this plan, via the established laws of causes and effects?

it appears, that the Divine Being decrees all future events. For he he gave such a nature to his creatures, and placed them in such circumstances, that a certain train of actions behoved necessarily to follow9

We won’t get much more of an answer as to how these things work themselves out.

Having advanced the “doctrine of universal necessity”, Lord Kames then moves to “unravel the curious mystery” as to why we have “feelings of contingency and liberty” which are contrary to “the truth of things.” It is the way Kames attempts to solve this particular mystery that will draw rebukes, albeit from differing perspectives, from both Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley.

Lord Kames will argue that mankind must think we have within us the power over our own actions for without it we cannot fulfill our prescribed roles in God’s plan.

It is certain, that, in our ordinary train of thinking, things never occur to us [as being necessitated by fixed laws]. A multitude of events appear to us as depending upon ourselves to cause or to prevent: and we readily make a distinction betwixt events, which are necessary, i.e. which must be, and events which are contingent, i.e. which may be, or may not be. This distinction is without foundation in truth: for all things that fall out, either in the natural or moral world, are, as we have seen, alike necessary, and alike the result of fixed laws. Yet … we act universally upon this supposed distinction. Nay; it is in truth the foundation of all the labor, care and industry of mankind.10

It is unclear why we must have this “deceitful feeing”, which is contrary to the truth, when it seems it would have been possible for God to organize the train of causes and effects to have us act our part regardless.

In this plan [formed in the infinite mind of The Deity], man, a rational creature, was to bear his part, and to fulfill certain ends, for which he was designed. He was to appear as an actor, and to act with consciousness and spontaneity. He was to exercise thought and reason, and to receive the improvements of his nature, by the due use of these rational powers. Consequently it was necessary, that he should have some idea of liberty; some feeling of things possible and contingent, things depending upon himself to cause, that he might be led to a proper exercise of that activity, for which he was designed.11

He summarizes this a bit later:

In short, reason and thought could not have been exercised in the way they are, that is, man could not have been man, had he not been furnished with a feeling of contingency. … Man must be so constituted, in order to attain the proper improvement of his nature, in virtue and happiness. 12

The “feeling of contingency” is what appears to ground our conception of moral responsibility.

His happiness and misery appear to be in his on power. He appears praiseworthy or culpable, according as he improves or neglects his rational faculties. The idea of his being an accountable creature arises. Reward seems due to merit; punishment to crimes. He feels the force of moral obligation.13

It is these statements that form the third and fourth premises in Wesley’s argument against Kames. 14 They certainly suggest a struggle within Lord Kames regarding the compatibility of moral responsibility and necessity.

This solution seems particularly odd given he will assert that virtue and vice have a firm and separate foundation beyond these feelings – the sensibility that virtue is preferable to vice as part of the “just order”.15 It seems, given his view of the necessity of all actions, that this foundation would have been the one worth exploring and to building upon. But that solution would not have accounted for the unmistakable fact that we think we have a power of contingency.

Therefore Lord Kames draws the conclusion that there was no other way to bring about the plan conceived in the infinite mind of God, nor to move men to virtue. This “feeling of contingency” also called an “artificial light” is a “most fit and wise” way for the universe to be governed. It possesses a “peculiar glory.”

For the above described artificial sense of liberty, is wholly contrived to support virtue, and to give its dictates the force of a law. Hereby it is discovered to be, in a singular manner, the care of the Deity; and a peculiar sort of glory is thrown around it. … [Virture] could not otherways be brought about, but by means of the deceitful feeling of liberty, which therefore is a greater honour to virtue, a higher recommendation of it, than if our conceptions were, in every particular, correspondent to the truth of things.16

The curious mystery is solved. But at what cost. Wesley, in his essay Thoughts Upon Necessity, published in 1774, was certainly right in concluding has he “not fairly giving up the whole cause.”

Wesley wasn’t the only one to weigh in.

Lord Kames published Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion: In Two Parts, in 1751, three years before Jonathan Edwards more famous treatise Freedom of the Will. Edwards responded to Lord Kames in 1758 in a short essay titled Remarks on Lord Kames’ Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion. These remarks appear at the end of many editions of Freedom of the Will. 17

Jonathan Edwards provides a most well grounded and justified summary of Lord Kames’ view which asserts that “moral necessity or certainty that attends men’s actions” is inconsistent with praise and blame, reward and punishment.

The Author of the Essays supposes, that God has deeply implanted in Man’s Nature, a strong and invincible Apprehension, or Feeling, as he calls it, of a Liberty and Contingence of his own Actions, opposite to that Necessity which truly attends them; and which in Truth don’t agree with real Fact, is not agreeable to strict philosophic Truth, is contradictory to the Truth of Things, and which Truth contradicts, not tallying with the real Plan: and that therefore such Feelings are deceitful, are in Reality of the delusive Kind.

He speaks of them as a wise Delusion, as nice artificial Feelings, merely that Conscience may have a commanding Power: meaning plainly, that these Feelings are a cunning Artifice of the Author of Nature, to make Men believe they are free, when they are not. He supposes that by these Feelings the moral World has a disguised Appearance. And other Things of this Kind he says.18

Despite both holding to Reformed doctrines and a common principle of acting on the strongest desire, clearly Edwards did not view the essay favorably. That will be the topic for another post.

[Continuing Thoughts Upon Necessity (part 3)]

- quote taken from Edwards Remarks p14 ↩︎

- A version of Kames essay can be found in archive.org

https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_essays-on-the-principles_kames-henry-home-lord_1751 ↩︎ - Kames p156 ↩︎

- Ibid p162-163 ↩︎

- Ibid mes p167 ↩︎

- Ibid p168-169 (see also page 179-180 where he adds a summary of the argument to that point) ↩︎

- Ibid 174 ↩︎

- Ibid p187-188 ↩︎

- Ibid 181 ↩︎

- Ibid 183-185 ↩︎

- Ibid 188-189 ↩︎

- Ibid 190, 204 ↩︎

- Kames 206-207 ↩︎

- https://deadheroesdontsave.com/2025/01/16/wednesday-with-wesley-thoughts-upon-necessity/ ↩︎

- Ibid 208-210 ↩︎

- Ibid 210-211 ↩︎

- An online edition of Edwards’ Remarks

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=3fVhAAAAcAAJ&pg=GBS.PA1&hl=en ↩︎ - Edwards p8 (from cited online edition) ↩︎

Just letting you know I’m reading this series on Wesley and Kames. It is interesting.

Good to hear from you Paul

It has been awhile, hope all is well

Thanks for the encouragement. There is probably one or two more posts as I engage with Edwards’ remarks and then Wesley’s brief interaction with Edwards