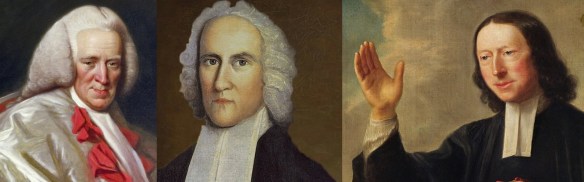

This post is part 5 of a series that has explored the three essays on the topic Liberty and Necessity by John Wesley, Jonathan Edwards and Lord Kames. This series started with this post Wednesday with Wesley: Thoughts Upon Necessity

This series started with a look at John Wesley’s critique of the Lord Kames’ views on Necessity, Liberty and Moral Obligation. Wesley focused on two aspects of Lord Kames’ view and contrasted them with the theme of judgment in Scripture. The first was that Kames required a Liberty of Contingence for there to be moral accountability and the second was that, according to the Scot, we don’t have it.

Despite a good deal of agreement between Lord Kames and Jonathan Edwards, particularly on our actions being morally necessary, we found that Edwards assailed the position held by Lord Kames as well. The main point Edwards made was that we do have liberty, but it is not a Liberty of Contingence. He would then argue that a Liberty of Moral Necessity was not only compatible with moral accountability for our actions, but that it is the only rational way to defend that we are under Moral Obligation.

As, Wesley, in his essay, has laid out the final conclusions against the Lord Kames (see part 1), he writes “Mr. Edwards has found out a most ingenious way of evading this consequence.”1 This “most ingenious way” around Wesley’s conclusion was to argue with “deep, metaphysical reasoning” for a different definition of liberty. Anyone who has tackled Edward’s Inquiry would have to agree with Wesley, it is a dense treatise that specializes in the wrangling of words and ideas.

Wesley does not directly quote Edwards but does correctly identify how he escapes the predicament of Lord Kames’ position.

Such absurdities [as a judgment when men are not morally accountable] follow, from the scheme, of Necessity. But Mr, Edwards, has found a most ingenious way of evading this consequence. …. if the actions of men were involuntary, the consequence would inevitably follow; they could not be either good or evil … [but]… The actions of men are quite voluntary; the fruit of their own will. … Now if men voluntarily commit theft, adultery or murder, certainly the actious are evil, and therefore punishable. And if they voluntarily serve GOD, and help their neighbors, the actions are good, and therefore rewardable. 2

Edwards claims that our actions, despite being morally necessary, are voluntary choices. Therefore we should be morally accountable for them.

Wesley, in crafting his summary, may have drawn on Edward’s clear assertions that the act of the Will, consisting of “some inclination of the soul”, is voluntary action. 3

the Will’s determining between [one thing rather than another], is a voluntary determination; but that is the same thing as making a choice. 4

and

There is scarcely a plainer and more universal dictate of the sense and experience of mankind, than that, when men act voluntarily, and do what they please, then they do what suits them best, or what is most agreeable to them. 5

If we remember, Edwards has defined Liberty as the power to do as one pleases. That is equated, here, with the idea of acting voluntarily. Later in his Inquiry, Edwards ties having liberty to having moral accountability.

The common people, in their notion of a faulty or praiseworthy deed or work done by any one, do suppose that the man does it in the exercise of liberty. But then their notion of liberty is only a person’s having opportunity of doing as he pleases. … the more he does either with full and strong inclination, the more is he esteemed or abhorred, commended or condemned.6

Stepping back, Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley, and even the Lord Kames, can be said to affirm that liberty is necessary for moral accountability. However, the differences in how these theologians define and understand the term liberty render this statement meaningless as it is rife with semantic ambiguity. Further exploration is required as each is saying something quite different than the other.

Continue reading