This is part 10 of the series blogging through the book On the Incarnation by Athanasius. You might want to start with part 1 and work your way through the series.

As we have noted, a careful reading, and, at least in my case, several re-readings of On the Incarnation reveals major themes in Athanasius’ theology. Over the course of both this work and its prequel he has laid out a foundation and has continually built upon it as he makes his case for the Incarnation and why it was necessary. In this post we will unpack the second dilemma that necessitated the Incarnation of the Word.

The Good Life is found in Contemplation

In Against the Gentiles, Athanasius described the proper state of human existence as a relationship with God rooted in contemplation (see part 2). By using our rational facilities to focus on the things above we may learn and understand “divine realities”. For Athanasius the Fall was the result of humans taking our focus away from the things above and directing it towards lower or more worldly things. In chapter 11 of On the Incarnation, Athanasius reiterates these ideas in laying out the basis for the second dilemma.

Just as mankind as a created being was mortal by nature, Athanasius will argue, we are also unable by nature (as originally created) to know or receive knowledge about the Creator. But God, desiring to be known, bestowed mankind with His own image. Among all the things that being made in the image of God might entail. it refers to God’s providing us with a rational soul from which He can be contemplated and perceived. This ability was what separated humans from the rest of the “irrational” creatures.

creating human beings not simply like all the irrational animals upon the earth but making them according to his own image, giving them a share of the power of his own Word, so that … being made rational, they might be able to abide in blessedness, living the true life

(chap 3) 1

The blessed life was to know the Creator.

being good he bestowed on them of his own image … so that … knowing the Creator they might live the happy (εὐδαίμονα) and truly blessed life.

(chap 11)2

The rational soul could know God through contemplation of the Image, which is another way Athanasius will refer to the Word. In using our reason rightly to contemplate the Word, a person could then receive a better understanding of the Father. This would in turn result in a happy and blessed life.

When Athanasius refers to the happy and blessed life he uses the Greek word εὐδαίμονα. 3

καὶ γινώσκοντες τὸν ποιητὴν ζῶσι τὸν εὐδαίμονα καὶ μακάριον ὄντως βίον 4

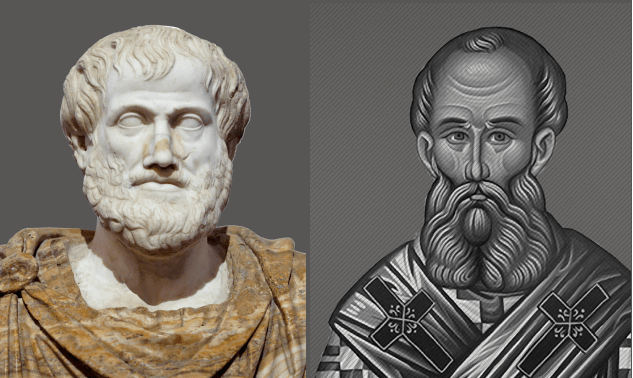

This Greek word is the same word Aristotle would use, along with the noun εὐδαιμονία, to describe human flourishing or the good life. For both Aristotle and Athanasius a happy life is the result of using our ability to reason well. Using our intellect rightly was considered the highest good. 5

In trying to understand Athanasius’ idea of contemplation I found that his theology has echoes of Aristotle’s philosophy. For Athanasius, humans have a rational facility that separates them from the animals. This facility, when used well, will contemplate on the the Word, which would lead to knowing God and living a life of virtue. This was, for Athanasius, the highest good.

They could also by knowing the law (here referring to the Scriptures) cease from all lawlessness and live the life of virtue

(chap 12).6

Aristotle saw the superior activity of the gods as contemplation and the primary difference between mankind and the animals as the ability to be rational like the gods. 7 Aristotle further understood the highest end for a person was to use their rational facilities to pursue and ultimately achieve εὐδαιμονία. In Book I.7 of his Nichomean Ethics, he would assert that the “human good” is an “activity of the soul (rationality) in accord with virtue”.

Later he would write that the wise person is the one that uses their rational intellect well and achieves a happy life.

But the person who is active in accord with the intellect, who cares for this and is in the best condition regarding it, also seems to be dearest to the gods. For if there is a certain care for human things on the part of the gods, as in fact there is held to be, it would also be reasonable for gods to delight in what is best and most akin to them – this would be the intellect – and to benefit in return those who cherish this above all and honor it, on the grounds that these latter are caring for what is dear to gods as well as acting correctly and nobly. And that all these things are available to the wise person especially is not unclear. He is dearest to the gods, therefore, and it is likely that this same person is also happiest (εὐδαιμονέστατον). As a result in this way too, the wise person would be especially happy (εὐδαίμων). 8

(Nichomean Ethics Book X.8 (1179a 20-30))

In comparing these ideas we find that both Aristotle and Athanasius find rationality and reason used well as central to living a virtuous life and achieving εὐδαιμονία. Understanding that Athanasius was formulating Aristotle’s ideas on human flourishing from a Christian perspective can help us grasp what he meant by contemplation and give us better insight into what he sees as a necessary part of the Incarnation.

The Second Dilemma

The second dilemma as framed by Athanasius is related to how humans are using their rationality or intellect. Humans used their rationality poorly and turned away from God. The result was they fell deeper and deeper into wickedness and no longer knew their Creator. If knowing the Creator was the basis for a happy and blessed life (εὐδαιμονία) then people are no longer flourishing as God intended.

Since, then, human beings had become so irrational and demonic deceit was thus overshadowing every place and hiding the knowledge of the true God, what was God to do?

(chap 13)9

Athanasius, asserts that God gave us the ability to know Him within ourselves by virtue of being made in the image. But God also knew we were weak & careless, so He made available multiple ways in which He might be known.

These included:

- The grace of being in the image, which Athanasius argues is “sufficient to know the God Word”.

- the harmony of creation

- the providence of God in creation

- the law and the prophets

Despite all of these ways that God made available to make Himself known, humans were still drawn by worldly things and, ignoring the means provided, did not know Him. Instead they traded the Creator for the created, and turned to wickedness and idolatry, the major theme for the prequel to On the Incarnation.

Athanasius argues that God could neglect humans and leave them in their state of ignorance, but this would be improper. If God did nothing, leaving humans in their ignorance, then what need was there for God to create humans as rational agents in the first place. If in the end He was just going to let them remain in an irrational state then it would have been better not to have given them the gift of being in the image and to have left them as irrational like the animals. It also would be improper, Athanasius adds, for God, desiring to be known, to remain unknown.

God, Athanasius asserts, needed to “renew” in us “again the ‘in the image’ so that through this human beings would be able to once again know him.” To accomplish this, the Word, who is also the Image of the Father, was sent. Athanasius refers to the soul being recreated after the image as being “born again”. Given the modern way we understand the term “born again” it is unclear exactly what Athanasius envisions here. The rest of this section will describe how Jesus came to teach us through miracles and works in the body so that He could overcome all the perceptions we have that distract us from contemplating the Word. This implies that this “renewing” was accomplished through Jesus’ teaching ministry on earth and through His death and resurrection.

For since human beings, having rejected the contemplation of God …[are] seeking God in creation and things perceptible, setting up for themselves mortal humans and demons as gods, for this reason the lover of human beings and the common Savior of all, takes to himself a body and dwells as human among humans and draws to himself the perceptible senses of all human beings

(chap 15)10

The way the Word would draw all people to Himself was through the working of miracles and in His resurrection. When humans, intent on focusing their perceptions on things of the world, saw that the Word in the body was doing works that overshadowed any other person that ever lived, healing the lame and blind, casting out demons, ruling over creation itself and even conquering death they might then redirect their attention to the Word who would then direct them to the true God. As they focused their rational facilities on divine realities they would know their Creator again and be able to live a happy life.

since human beings did not know his providence in all things nor understand his divinity through his creation, if they looked up on account of his works done through the body they might gain a notion through him of the knowledge of the Father (chap 19)11

As Athanasius refutes the unbelief of Jews and the mockery of the Greeks later in the work, he reiterates these points, iterating over all of the ways Jesus showed Himself superior over demons, creation, Hades and death while in the body. In this way Jesus left no part of creation, which people were prone to turn into idols, untouched. In this way our perceptions, which are attuned to the world, may find an example of Jesus overcoming the worldly things that distract us. This is how Jesus was drawing us back to Him.

For if anyone wishes … he sees through his work his power incomparable to that of human beings and knows that he alone among human beings is the Word of God. … For the Lord touched all parts of creation and freed and disabused everything from every error … in order that no one might be any longer deceived, but might find everywhere the true Word of God. (chap 45)12

We are encouraged then to redirect our rational intellect on the Word and to focus on divine realties and to then live pursuing a life of virtue, knowing that we will be judged for what we have done in the body, whether good or evil.

The two works, Against the Gentiles and On the Incarnation, were originally written to strengthen the faith of those that already believed in Christ so that “no one may regard the teaching of our doctrine as worthless, or suppose faith in Christ to be irrational.”13 However, Athanasius also makes appeals to those who do not yet know Christ so that they may be drawn to the Word and ultimately share in all that He accomplished:

so let the one not believing the victory over death accept the faith of Christ and come over to his teaching, and he will see the weakness of death and the victory over it. (chap 28)14

[Fin]15

[Addendum on Free Will]

- Athanasius, Saint, Patriarch of Alexandria. On the Incarnation: Saint Athanasius (Popular Patristics Series Book 44) (p. 49). St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. Kindle Edition ↩︎

- Ibid (p. 58) ↩︎

- Entry in Perseus

https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=%CE%B5%E1%BD%90%CE%B4%CE%B1%CE%AF%CE%BC%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%B1&la=greek#Perseus:text:1999.04.0072:entry=eu)dai/mwn-contents ↩︎ - St. Athanasius on The incarnation, the Greek text

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=5sIUAAAAQAAJ&pg=GBS.PA16&hl=en ↩︎ - https://www.britannica.com/topic/eudaimonia ↩︎

- Athanasius, Saint, Patriarch of Alexandria. On the Incarnation: Saint Athanasius (Popular Patristics Series Book 44) (p. 59). St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. Kindle Edition ↩︎

- Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, A New Translation: Aristotle, Bartlett, Robert C, and Collins, Susan D. (p. 227-228). The University of Chicago Press (2011)

Book X.8 (1178b 20-25) ↩︎ - Ibid (p 229)

cross referenced with Greek edition

https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0053%3Abekker+page%3D1179a%3Abekker+line%3D30 ↩︎ - Athanasius, Saint, Patriarch of Alexandria. On the Incarnation: Saint Athanasius (Popular Patristics Series Book 44) (p. 60). St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. Kindle Edition ↩︎

- Ibid (p 63) ↩︎

- Ibid (p 68) ↩︎

- Ibid (p 100) ↩︎

- Ibid (p 15-16) quoting the prequel Against the Gentiles ↩︎

- Ibid (p 78) ↩︎

- Athanasius has three more sections in this work. One argues why the cross as a public execution was necessary. The other two sections are repetitive of many of the points already made as Athanasius appeals to Jews and Greeks to accept Jesus the Word Incarnate. As this series has gotten a bit long, I have decided to end the series here ↩︎