This is part 4 of the series blogging through the book On the Incarnation by Athanasius. You might want to start with part 1 and work your way through the series.

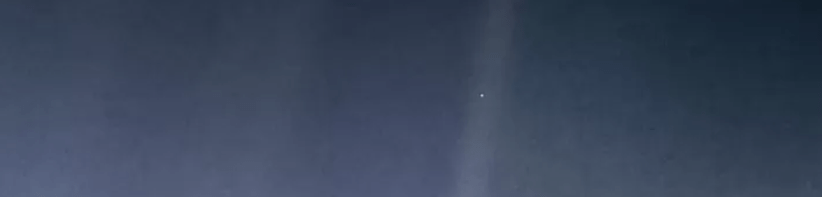

On Feb 14, 1990, Voyager 1 sent back its famous image of the “pale blue dot”, capturing how large and vast the universe is. This was taken some 3.7 billion miles from the sun as the probe left our solar system. 1 However, the idea that the universe was larger than our solar system, something we take for granted as a well established fact, was still a debated idea until Jan 1, 1925.2

When we affirm that the heavens declare the glory of God, we have a very different mental model and understanding of these heavens than Athanasius and his contemporaries did living in the fourth century. However, that doesn’t mean that in each age the creation doesn’t “make known, and witness to, the Father of the Word, Who is the Lord and Maker of these [things]” 3

In noting that “it is first necessary to speak about the creation of the universe and its Maker”, Athanasius quickly affirms creation ex nihilo, an act performed by the Father through the Word.

God is not weak, but from nothing and having absolutely no existence God brought the universe into being through the Word 3

On the Incarnation chap 3

In On the Incarnation, Athanasius explores creation as it relates to the incarnation and the cross. A topic that we will explore later in this series. In Against the Gentiles the emphasis is on how creation declares a Creator. It is in this earlier work that we get a brief description of how Athanasius understands the universe. That will be the focus on this particular entry in the blogging series.

For Athanasius, as noted already, the model of the universe was very different from what we know today. It would be incredibly smaller, at least from our point of view. In a prior series we explored ancient cosmology and the major characteristics from the point of view of a person living in the fourth century5

Continue reading