In part one we explored the concepts of existence and identity. That was followed, in part 2, by a look at the major influences that lead to the idea that the soul is immortal. This entry will explore alternative understandings of the soul for consideration.

In the last post we saw that, despite different underlying philosophical foundations, Augustine and Aquinas affirm that the person is a composite of body and soul. They also both affirm that the soul, an incorporeal intellect and the principle of life, is naturally immortal (or incorruptible). In a moment we will see that both theologians will be careful to ground the existence of the soul in God and His will rather then in itself. In doing so, we might, with a degree of irony, call both Augustine and Aquinas advocates of a conditional immortality.

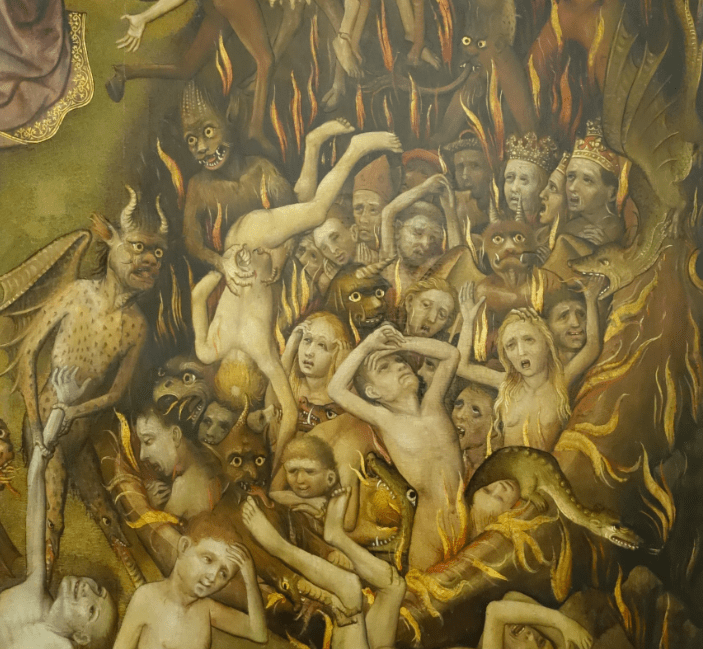

The punishment of the damned will never come to an end

Before one scoffs at that and considers it a foolish claim, let me make it abundantly clear that both of these theologians affirm that the wicked will suffer eternal conscious torment (ECT).

pain can exist only

in a living subject 1

– Augustine

Augustine notes that in his day there is debate about the fate of the wicked. He spends the greater part of Book XXI of The City of God making the case that “the soul [of the wicked] will neither be able to enjoy God and live, nor to die and escape the pains of the body.” 2

… to say in one and the same sense, life eternal shall be endless, punishment eternal shall come to an end, is the height of absurdity. Wherefore, as the eternal life of the saints shall be endless, so too the eternal punishment of those who are doomed to it shall have no end.3

In the supplement to the Summa Aquinas argues “the damned can prefer ‘not to be’ according to their deliberate reason” which would be to have “relief from a painful life”.4 However “it is inadmissible that the punishment of the damned will ever come to an end.” 5

The disposition of hell will be such as to be adapted to the utmost unhappiness of the damned. Wherefore accordingly both light and darkness are there, in so far as they are most conducive to the unhappiness of the damned. 6

Having established that Augustine and Aquinas were deeply committed to ECT, why might we consider them advocates of conditional immortality?

Continue reading