This post is the third part of a series looking at The Third Peacock. If you have not already read it, I recommend starting with part 1.

The introduction of the Incarnation to theodicy in The Third Peacock is a great answer to the question how will God deal with the evil and badness found in creation as well as telling us how God will “make a good show of creation.” It is a rather odd answer to questions like why does God permit so much evil in the first place. But at this point in the book Capon and his readers have “hit the bottom” as there is no way to get “God off the hook for evil”. Nor, for Capon, was the risk God took with freedom worth all the evil and badness.

In light of the reality of evil, Capon pivots and attempts to pull all of the threads he has been exploring – a theology of delight, freedom, badness and a personal yet hands off God – together.

Throughout the book Capon’s style seems designed to shock the reader and he continues this trend with the Incarnation.

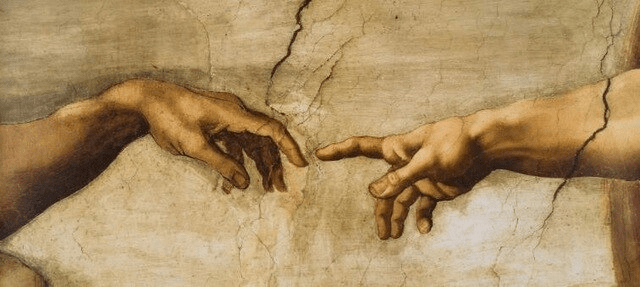

In the Christian scheme of things, the ultimate act by which God runs and rescues creation is the Incarnation. Sent by the Father and conceived by the Spirit, the eternal Word is born of the Virgin Mary and, in the mystery of that indwelling, lives, dies, rises and reigns. Unfortunately, however, we tend to look on the mystery mechanically. We view it as a fairly straight piece of repair work which became necessary because of sin.

Capon isn’t dismissing the fact that Jesus came in the flesh to deal with sin, but he is asking us to consider it as much more. In doing so Capon is drawing on a historical view of the Incarnation that is not widely held or discussed. Prior to reading this book I was not familiar with it. The view has been described as Unconditional Incarnation as well as Supralapsarian Christology.

Continue reading →