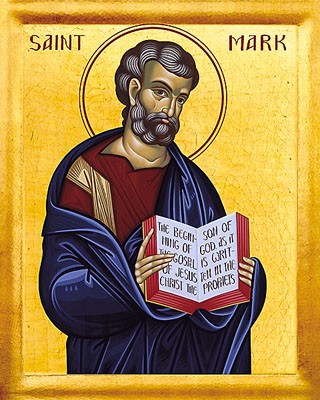

The earlier posts in this series (part 1) explored the early evidence that a person named Mark is the author of the book we call the Gospel of Mark.

The testimony was largely in agreement about the following information:

- Mark was the author.

- Mark was not a disciple of Jesus (while Jesus was alive).

- Mark wrote down what Peter was teaching and proclaiming.

- The book was written at the request of believers in Rome.

The testimony of the early church also notes that Mark was in Alexandria, Egypt planting churches.

Who is this person named Mark?

The extant testimony of the early church is unanimous that it was written by Mark, a person taken to be John Mark, the associate of Barnabas and Paul on the 1MJ.

One factor in favor of this being correct, notes Daniel Wallace, is that Mark is “by no means a major player in the New Testament.”1

The author identified as Mark is widely accepted as the person named John Mark that we find referenced throughout the NT.

In The New Testament in Its World, affirms that no alterative person has ever been suggested as the author.

Continue readingCertainty is impossible, but John Mark is probably the best candidate, not least because his name, as a younger and less well-known early Christian, would not naturally occur to second-century Christians when seeking to name the book. No alternative figure has ever warranted consideration. 2